|

| Photocredit: BA Antiquities Museum/C. Gerigk |

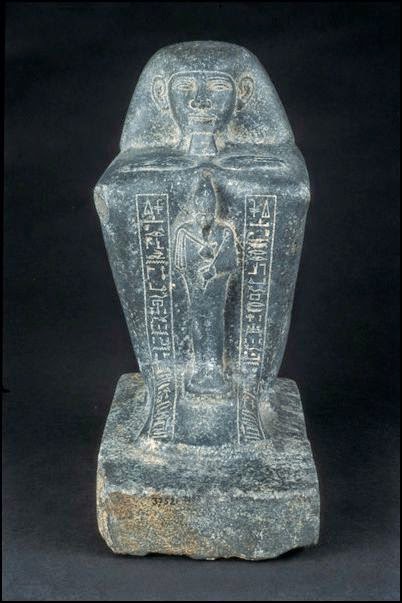

Category: Sculpture in the round, statues, human / gods and goddesses statues, block (cube) statues

Date: Late Period (664-332 BCE)

Provenance: Upper Egypt, Luxor (Thebes), East Bank, Karnak temple

Material(s): Rock, granite, black granite

Height: 46 cm; Width: 20.5 cm; Depth: 29.5 cm

Inventory#: BAAM Serial 0598

Description

Block statue of a priest serving the god Montu in Thebes by the name of "Nes Amun" which was found in a cache in Karnak. The priest is represented in a squatting position and a relief sculpture of the god of the dead, Osiris in mummified form and wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt, occupies the centre of the statue. The god Osiris holds the crook and flail, emblems of power and government. Hieroglyphs in two vertical lines on the sides glorify him. The back of the statue also contains hieroglyphs divided into two horizontal lines which read from right to left representing a dedication from the priest and prayers for his soul.

The Priesthood

The priest in ancient Egypt was considered a servant of the god and he was therefore referred to as Hem-Neter, Hem literally meaning servant, Neter meaning god. He was attached to a temple to look after the needs of the god in terms of food and clothing. During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, some priests worked only part-time at the temple and returned to their ordinary everyday family life and occupation after a stint lasting three months in the temple compound (one month in every four per year).

Priests were divided into different ranks and had different duties within the temple, such as attending to offerings and minor parts of temple ritual, or running the economic affairs and administration of the temple, while only the chief priest was allowed to handle the cult image. This high rank of priesthood was not limited to men only, as women from the elite also filled the role of chief priestess. They were called Hemet-Neter and during the Old and Middle Kingdom served the goddess Hathor.

The chief priest exercised great power and influence on Pharaoh and ordinary people alike. During the 18th Dynasty (1550-1295), the god Amun gained supremacy over other gods and as a result, the Amun priesthood dominated the religious landscape and became exceedingly powerful.

The lowest or entry rank among priests was that of Waab, or 'purifier' who was entrusted with the purification and cleanliness of ritual area and items, however, he was not allowed into the inner sanctuary. Another rank of priesthood was that of astrologer/ astronomer which was in charge of divination and of calculating time and setting the calendar determining religious festivals, as well as lucky and unlucky days.

Other priests attached to the "House of Life" or 'Per-Ankh' were responsible for teaching religious matters, writing and for copying texts. The Hery Heb or lector priests recited the words of the god. They were part of the permanent staff at the temple.

Every temple had its retinue of singers and musicians to perform during festivals and rituals. Women among the nobles had the title of "singer or chantress of Amun" and were shown holding or shaking the musical instrument called sistrum during ceremonial activities.

There were other priests involved with healing, with oracles, those who were able to communicate with the dead (mainly women called Rakhet) and those workers of protective magic.

Priests were not allowed to wear wool or leather products, only clothes made of high-quality linen and sandals made of Papyrus, with the exception of the Sem priests who wore a cheetah skin. The latter performed the 'Opening of the Mouth' ceremony during the mummification process.

Priests inherited their role from their fathers, and by the Roman period it was common for the office to be bought. The role of priests in small provincial temples remained less important than in larger ones.

Bibliography

"Priests". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Donald B. Redford. Vol. III. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

"Priests". In Dictionary of Egyptian civilization. By Posener, Georges, Serge Sauneron and Jean Yoyotte. Translated from the French by Alix Macfarlane. London: Methuen, 1962.

Source: http://antiquities.bibalex.org/Collection/Detail.aspx?lang=en&a=598