Akhenaten upended the religion, art, and politics of ancient Egypt, and then his legacy was buried. Now he endures as a symbol of change.

By Peter Hessler

Photograph by Rena Effendi

Sometimes the most powerful commentary on a king is made by those who are silent. One morning in Amarna, a village in Upper Egypt about 200 miles south of Cairo, a set of delicate, sparrowlike bones were arranged atop a wooden table. “The clavicle is here, and the upper arm, the ribs, the lower legs,” said Ashley Shidner, an American bioarchaeologist. “This one is about a year and a half to two years old.”

The skeleton belonged to a child who lived at Amarna more than 3,300 years ago, when the site was Egypt’s capital. The city was founded by Akhenaten, a king who, along with his wife Nefertiti and his son, Tutankhamun, has captured the modern imagination as much as any other figure from ancient Egypt. This anonymous skeleton, in contrast, had been excavated from an unmarked grave. But the bones showed evidence of malnutrition, which Shidner and others have observed in the remains of dozens of Amarna children.

“The growth delay starts around seven and a half months,” Shidner said. “That’s when you start transition feeding from breast milk to solid food.” At Amarna this transition seems to have been delayed for many children. “Possibly the mother is making the decision that there’s not enough food.”

Until recently Akhenaten’s subjects seemed to be the only people who hadn’t weighed in on his legacy. Others have had plenty to say about the king, who ruled from around 1353 B.C. until 1336 B.C. and tried to transform Egyptian religion, art, and governance. Akhenaten’s successors were mostly scathing about his reign. Even Tutankhamun—whose brief reign has been a subject of fascination since his tomb was discovered in 1922—issued a decree criticizing conditions under his father: “The land was in distress; the gods had abandoned this land.” During the next dynasty, Akhenaten was referred to as “the criminal” and “the rebel,” and pharaohs destroyed his statues and images, trying to remove him from history entirely.

Showing posts with label Amun. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Amun. Show all posts

Friday, August 25, 2017

Thursday, April 23, 2015

The Cult of Amun

In the epic rivalry between ancient Egypt and Nubia, one god had enduring appeal

By Daniel Weiss

In its 3,000-year history as a state, ancient Egypt had a complicated, constantly changing set of relations with neighboring powers. With the Libyans to the west and the Babylonians, Hittites, Assyrians, and Persians to the northeast, Egypt by turns waged war, forged treaties, and engaged in mutually beneficial trade. But Egypt’s most important and enduring relationship was, arguably, with its neighbor to the south, Nubia, which occupied a region that is now in Sudan. The two cultures were connected by the Nile River, whose annual flooding made civilization possible in an otherwise harsh desert environment. Through their shared history, Egyptians and Nubians also came to worship the same chief god, Amun, who was closely allied with kingship and played an important role as the two civilizations vied for supremacy.

During its Middle and New Kingdoms, which spanned the second millennium B.C., Egypt pushed its way into Nubia, ultimately conquering and making it a colonial province. The Egyptians were drawn by the land’s rich store of natural resources, including ebony, ivory, animal skins, and, most importantly, gold. As they expanded their control of Nubia, the Egyptians built a number of temples to Amun, the largest of which stood at the foot of a holy mountain called Jebel Barkal. This the Egyptians declared to be the god’s southern home, thereby conceptualizing Egypt and Nubia as a unified whole and justifying their rule of both. After Egypt’s New Kingdom collapsed around 1069 B.C., the kingdom of Kush rose in Nubia, with its court based in Napata, the town adjacent to Jebel Barkal. The Egyptian colonizers may have been gone, but their religious legacy lived on, as the Kushite rulers were by this time fervently devoted to Amun. Just as the Egyptians had used the god to validate their conquest of Nubia, the Kushites now returned the favor. During a period of discord in Egypt, the Kushite king Piye first secured Amun’s northern home, in Karnak, Egypt. Then, claiming to act on the god’s behalf to restore unified control of Nubia and Egypt, he conquered the rest of Egypt and, in 728 B.C., became the first in a line of Kushite pharaohs who ruled Egypt for around 70 years.

By Daniel Weiss

In its 3,000-year history as a state, ancient Egypt had a complicated, constantly changing set of relations with neighboring powers. With the Libyans to the west and the Babylonians, Hittites, Assyrians, and Persians to the northeast, Egypt by turns waged war, forged treaties, and engaged in mutually beneficial trade. But Egypt’s most important and enduring relationship was, arguably, with its neighbor to the south, Nubia, which occupied a region that is now in Sudan. The two cultures were connected by the Nile River, whose annual flooding made civilization possible in an otherwise harsh desert environment. Through their shared history, Egyptians and Nubians also came to worship the same chief god, Amun, who was closely allied with kingship and played an important role as the two civilizations vied for supremacy.

During its Middle and New Kingdoms, which spanned the second millennium B.C., Egypt pushed its way into Nubia, ultimately conquering and making it a colonial province. The Egyptians were drawn by the land’s rich store of natural resources, including ebony, ivory, animal skins, and, most importantly, gold. As they expanded their control of Nubia, the Egyptians built a number of temples to Amun, the largest of which stood at the foot of a holy mountain called Jebel Barkal. This the Egyptians declared to be the god’s southern home, thereby conceptualizing Egypt and Nubia as a unified whole and justifying their rule of both. After Egypt’s New Kingdom collapsed around 1069 B.C., the kingdom of Kush rose in Nubia, with its court based in Napata, the town adjacent to Jebel Barkal. The Egyptian colonizers may have been gone, but their religious legacy lived on, as the Kushite rulers were by this time fervently devoted to Amun. Just as the Egyptians had used the god to validate their conquest of Nubia, the Kushites now returned the favor. During a period of discord in Egypt, the Kushite king Piye first secured Amun’s northern home, in Karnak, Egypt. Then, claiming to act on the god’s behalf to restore unified control of Nubia and Egypt, he conquered the rest of Egypt and, in 728 B.C., became the first in a line of Kushite pharaohs who ruled Egypt for around 70 years.

Thursday, March 5, 2015

News this week

By Rany Mostafa

Tomb of ‘gatekeeper of God Amun’ unearthed in Luxor

A 3,500-year-old tomb of “the gatekeeper of God Amun” has been unearthed in the west bank of Luxor, Antiquities Minister Mamdouh el-Damaty announced Tuesday.

The tomb was accidentally discovered during cleaning and restoration work carried out by the archaeology mission of the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) in a nearby tomb in the archaeological site of Sheikh Abd el Qurna on the west bank of Luxor, according to Damaty.

“The gatekeeper of Amun, one of several titles that were found carved at the tomb’s door lintel, is strongly believed to be a job description of an 18th Dynasty (1580 B.C.- 1292 B.C.) high official. Amenhotep is the real name of the tomb owner that was found carved at the walls of the tomb,” he added.

According to Damaty, the tomb measures 5 meters long by 1.5 meters wide and takes a T-shape. A small side chamber of 4 square meters with a burial shaft in the middle is to be found inside the tomb.

Sultan Eid, Director of Upper Egypt Antiquities Department told The Cairo Post Tuesday that some parts of the tombs are well preserved with “dazzling scenes showing Amenhotep, along with his wife, depicted standing making an offering before several ancient Egyptian deities.”

Tomb of ‘gatekeeper of God Amun’ unearthed in Luxor

A 3,500-year-old tomb of “the gatekeeper of God Amun” has been unearthed in the west bank of Luxor, Antiquities Minister Mamdouh el-Damaty announced Tuesday.

The tomb was accidentally discovered during cleaning and restoration work carried out by the archaeology mission of the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) in a nearby tomb in the archaeological site of Sheikh Abd el Qurna on the west bank of Luxor, according to Damaty.

“The gatekeeper of Amun, one of several titles that were found carved at the tomb’s door lintel, is strongly believed to be a job description of an 18th Dynasty (1580 B.C.- 1292 B.C.) high official. Amenhotep is the real name of the tomb owner that was found carved at the walls of the tomb,” he added.

According to Damaty, the tomb measures 5 meters long by 1.5 meters wide and takes a T-shape. A small side chamber of 4 square meters with a burial shaft in the middle is to be found inside the tomb.

Sultan Eid, Director of Upper Egypt Antiquities Department told The Cairo Post Tuesday that some parts of the tombs are well preserved with “dazzling scenes showing Amenhotep, along with his wife, depicted standing making an offering before several ancient Egyptian deities.”

Labels:

18th Dynasty,

Akhmim,

Amun,

Archaeology,

Horus Road,

Luxor,

Sites,

Tell Habua,

Theft and Looting,

Thutmose II,

Tomb

Tuesday, October 14, 2014

UCLA Egyptologist gives new life to female pharaoh from 15th century B.C.

No usurper, Hatshepsut was just really good at her job, according to new biography

By Meg Sullivan | October 08, 2014

By the time of her death in 1458 B.C., Egypt’s Pharaoh Hatshepsut had presided over her kingdom’s most peaceful and prosperous period in generations. Yet by 25 years later, much of the evidence of her success had been erased or reassigned to her male forebears.

Even after 20th century archaeologists began to unearth traces of the woman who defied tradition to crown herself as king, Hatshepsut still didn’t get her due, a UCLA Egyptologist argues in a forthcoming book.

“She’s been described as a usurper, and the obliteration of her contributions has been attributed to a backlash against what has been seen as her power-grabbing ways,” said Kara Cooney, the author of “The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt.”

In the mainstream biography, due Oct. 14 from Crown Publishing, Cooney sets out to rehabilitate the reputation of the 18th dynasty ruler whom she considers to be “the most formidable and successful woman to ever rule in the Western ancient world.” To find a parallel, Cooney argues, one has to look to Empress Lü of third century B.C. China, Elizabeth I or Catherine the Great.

“Hatshepsut’s story needs to be carefully resurrected and her modus operandi needs to be dissected and analyzed in a more fair-minded way,” said Cooney, an associate professor of Near Eastern languages and culture in the UCLA College. “I see her as a person who created her position based on her ability to do the job rather than her desire for it.”

By Meg Sullivan | October 08, 2014

By the time of her death in 1458 B.C., Egypt’s Pharaoh Hatshepsut had presided over her kingdom’s most peaceful and prosperous period in generations. Yet by 25 years later, much of the evidence of her success had been erased or reassigned to her male forebears.

Even after 20th century archaeologists began to unearth traces of the woman who defied tradition to crown herself as king, Hatshepsut still didn’t get her due, a UCLA Egyptologist argues in a forthcoming book.

“She’s been described as a usurper, and the obliteration of her contributions has been attributed to a backlash against what has been seen as her power-grabbing ways,” said Kara Cooney, the author of “The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt.”

In the mainstream biography, due Oct. 14 from Crown Publishing, Cooney sets out to rehabilitate the reputation of the 18th dynasty ruler whom she considers to be “the most formidable and successful woman to ever rule in the Western ancient world.” To find a parallel, Cooney argues, one has to look to Empress Lü of third century B.C. China, Elizabeth I or Catherine the Great.

“Hatshepsut’s story needs to be carefully resurrected and her modus operandi needs to be dissected and analyzed in a more fair-minded way,” said Cooney, an associate professor of Near Eastern languages and culture in the UCLA College. “I see her as a person who created her position based on her ability to do the job rather than her desire for it.”

Labels:

18th Dynasty,

Amun,

Biographies,

Hatshepsut,

Kingship,

Pharaohs,

Thutmose II,

Thutmose III,

Women

Sunday, September 7, 2014

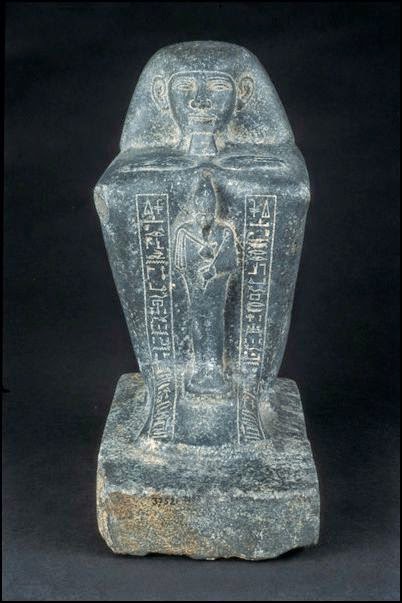

Museum Pieces - Block statue of Nes-Amun

|

| Photocredit: BA Antiquities Museum/C. Gerigk |

Category: Sculpture in the round, statues, human / gods and goddesses statues, block (cube) statues

Date: Late Period (664-332 BCE)

Provenance: Upper Egypt, Luxor (Thebes), East Bank, Karnak temple

Material(s): Rock, granite, black granite

Height: 46 cm; Width: 20.5 cm; Depth: 29.5 cm

Inventory#: BAAM Serial 0598

Description

Block statue of a priest serving the god Montu in Thebes by the name of "Nes Amun" which was found in a cache in Karnak. The priest is represented in a squatting position and a relief sculpture of the god of the dead, Osiris in mummified form and wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt, occupies the centre of the statue. The god Osiris holds the crook and flail, emblems of power and government. Hieroglyphs in two vertical lines on the sides glorify him. The back of the statue also contains hieroglyphs divided into two horizontal lines which read from right to left representing a dedication from the priest and prayers for his soul.

The Priesthood

The priest in ancient Egypt was considered a servant of the god and he was therefore referred to as Hem-Neter, Hem literally meaning servant, Neter meaning god. He was attached to a temple to look after the needs of the god in terms of food and clothing. During the Old and Middle Kingdoms, some priests worked only part-time at the temple and returned to their ordinary everyday family life and occupation after a stint lasting three months in the temple compound (one month in every four per year).

Priests were divided into different ranks and had different duties within the temple, such as attending to offerings and minor parts of temple ritual, or running the economic affairs and administration of the temple, while only the chief priest was allowed to handle the cult image. This high rank of priesthood was not limited to men only, as women from the elite also filled the role of chief priestess. They were called Hemet-Neter and during the Old and Middle Kingdom served the goddess Hathor.

The chief priest exercised great power and influence on Pharaoh and ordinary people alike. During the 18th Dynasty (1550-1295), the god Amun gained supremacy over other gods and as a result, the Amun priesthood dominated the religious landscape and became exceedingly powerful.

The lowest or entry rank among priests was that of Waab, or 'purifier' who was entrusted with the purification and cleanliness of ritual area and items, however, he was not allowed into the inner sanctuary. Another rank of priesthood was that of astrologer/ astronomer which was in charge of divination and of calculating time and setting the calendar determining religious festivals, as well as lucky and unlucky days.

Other priests attached to the "House of Life" or 'Per-Ankh' were responsible for teaching religious matters, writing and for copying texts. The Hery Heb or lector priests recited the words of the god. They were part of the permanent staff at the temple.

Every temple had its retinue of singers and musicians to perform during festivals and rituals. Women among the nobles had the title of "singer or chantress of Amun" and were shown holding or shaking the musical instrument called sistrum during ceremonial activities.

There were other priests involved with healing, with oracles, those who were able to communicate with the dead (mainly women called Rakhet) and those workers of protective magic.

Priests were not allowed to wear wool or leather products, only clothes made of high-quality linen and sandals made of Papyrus, with the exception of the Sem priests who wore a cheetah skin. The latter performed the 'Opening of the Mouth' ceremony during the mummification process.

Priests inherited their role from their fathers, and by the Roman period it was common for the office to be bought. The role of priests in small provincial temples remained less important than in larger ones.

Bibliography

"Priests". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Donald B. Redford. Vol. III. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

"Priests". In Dictionary of Egyptian civilization. By Posener, Georges, Serge Sauneron and Jean Yoyotte. Translated from the French by Alix Macfarlane. London: Methuen, 1962.

Source: http://antiquities.bibalex.org/Collection/Detail.aspx?lang=en&a=598

Labels:

Amun,

Art,

Block Statue,

Karnak,

Museum Pieces,

Nes-Amun,

Priests,

Statuary,

Temple cults,

Thebes

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Egyptian Carving Defaced by King Tut's Possible Father Discovered

By Owen Jarus, Live Science Contributor | July 24, 2014

A newly discovered Egyptian carving, which dates back more than 3,300 years, bears the scars of a religious revolution that upended the ancient civilization.

The panel, carved in Nubian Sandstone, was found recently in a tomb at the site of Sedeinga, in modern-day Sudan. It is about 5.8 feet (1.8 meters) tall by 1.3 feet (0.4 m) wide, and was found in two pieces.

Originally, it adorned the walls of a temple at Sedeinga that was dedicated to Queen Tiye (also spelled Tiyi), who died around 1340 B.C. Several centuries after Tiye's death — and after her temple had fallen into ruin — this panel was reused in a tomb as a bench that held a coffin above the floor.

Scars of a revolution

Archaeologists found that the god depicted in the carving, Amun, had his face and hieroglyphs hacked out from the panel. The order to deface the carving came from Akhenaten (reign 1353-1336 B.C.), a pharaoh who tried to focus Egyptian religion around the worship of the "Aten," the sun disk. In his fervor, Akhenaten had the name and images of Amun, a key Egyptian god, obliterated throughout all Egypt-controlled territory. This included the ancient land of Nubia, a territory that is now partly in Sudan.

"All the major inscriptions with the name of Amun in Egypt were erased during his reign," archaeology team member Vincent Francigny, a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, told Live Science in an interview.

The carving was originally created for the temple of Queen Tiye — Akhenaten's mother — who may have been alive when the defacement occurred. Even so, Francigny stressed that the desecration of the carving wasn't targeted against Akhenaten's own mom.

A newly discovered Egyptian carving, which dates back more than 3,300 years, bears the scars of a religious revolution that upended the ancient civilization.

The panel, carved in Nubian Sandstone, was found recently in a tomb at the site of Sedeinga, in modern-day Sudan. It is about 5.8 feet (1.8 meters) tall by 1.3 feet (0.4 m) wide, and was found in two pieces.

Originally, it adorned the walls of a temple at Sedeinga that was dedicated to Queen Tiye (also spelled Tiyi), who died around 1340 B.C. Several centuries after Tiye's death — and after her temple had fallen into ruin — this panel was reused in a tomb as a bench that held a coffin above the floor.

|

| Credit: Photo by V. Francigny © Sedeinga Mission |

Scars of a revolution

Archaeologists found that the god depicted in the carving, Amun, had his face and hieroglyphs hacked out from the panel. The order to deface the carving came from Akhenaten (reign 1353-1336 B.C.), a pharaoh who tried to focus Egyptian religion around the worship of the "Aten," the sun disk. In his fervor, Akhenaten had the name and images of Amun, a key Egyptian god, obliterated throughout all Egypt-controlled territory. This included the ancient land of Nubia, a territory that is now partly in Sudan.

"All the major inscriptions with the name of Amun in Egypt were erased during his reign," archaeology team member Vincent Francigny, a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, told Live Science in an interview.

The carving was originally created for the temple of Queen Tiye — Akhenaten's mother — who may have been alive when the defacement occurred. Even so, Francigny stressed that the desecration of the carving wasn't targeted against Akhenaten's own mom.

Sunday, January 26, 2014

Museum Pieces - Statue of Amun

|

| Photocredit: The Walters Art Museum |

PERIOD

1550-1069 BC (New Kingdom)

MEDIUM

cast bronze

(Metal)

ACCESSION NUMBER

54.481

MEASUREMENTS

H: 6 1/4 in. (15.8 cm)

GEOGRAPHY

Mitrahina, Egypt (Place of Discovery)

About Amun:

(Amoun, Amon, Amen, Ammon) ‘The Hidden’, a Theban God who rose to the pinnacle of national prominence, particularly in fusion with the Heliopolitan solar God Re as the fusion deity ‘Amun-Re’. The main temple of Amun at Karnak remains the largest religious structure ever built. Amun is depicted typically as a man with deep blue or black skin, wearing a crown with two high segmented plumes, and sometimes ithyphallic. His sacred animal is the ram with curved horns (Ovis platyura aegyptiaca, as distinct from the ram associated with Banebdjedet, Arsaphes, and Khnum, Ovis longipes palaeoaegypticus) and he can be depicted as a man with a ram’s head. Amun’s consort, aside from his female complement Amaunet, whose chief importance is in the context of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad, is Mut and their son is Khonsu. Regardless of the political factors which brought Amun to prominence as the city of Thebes became more powerful, and which maintained his prominence for the rest of Egyptian history as a symbol of national unity, Amun’s ability to exercise such broad appeal can be traced to the potency of the concept of a God of hiddenness as such, particularly at a time (the Middle Kingdom and later) when Egyptian society was engaged in speculative thought of increasing sophistication.

Sources: http://art.thewalters.org/detail/26134/amun-3/

http://henadology.wordpress.com/theology/netjeru/amun/

Saturday, January 11, 2014

More mysteries of Tutankhamun

The mystery of the ancient Egyptian Boy King Tutankhamun continues to fascinate Egyptologists as a new controversy reveals, writes Nevine El-Aref

This week the ancient Egyptian boy king Tutankhamun is in the limelight once again, with the image of his golden mask decorated with precious stones featuring in many international magazines and newspapers.

However, the current interest in the boy king is not because of his treasured funerary collection, his lineage, or the causes behind his early death, but instead because of the way in which he was mummified.

According to a study carried out by professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo (AUC) Salima Ikram, Tutankhamun was unusually embalmed by priests of the god Amun in an attempt to quash the religious revolution carried out by his father and predecessor the monotheistic king Akhnaten.

The latter had called for the worship of only one deity, the sun god Aten, and the abandonment of the ancient Egyptians’ other gods.

When Akhnaten’s son Tutankhamun came to the throne, he returned Egypt to its traditional religion of worshipping a diverse set of deities at the top of which was the god Amun.

To ensure that this conversion continued after Tutankhamun’s death and to abort any further religious revolution, Ikram suggests in her paper that the priests mummified Tutankhamun’s corpse in an unusual way to make him appear as Osiris, the god of the afterlife and the land of Egypt.

This week the ancient Egyptian boy king Tutankhamun is in the limelight once again, with the image of his golden mask decorated with precious stones featuring in many international magazines and newspapers.

However, the current interest in the boy king is not because of his treasured funerary collection, his lineage, or the causes behind his early death, but instead because of the way in which he was mummified.

According to a study carried out by professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo (AUC) Salima Ikram, Tutankhamun was unusually embalmed by priests of the god Amun in an attempt to quash the religious revolution carried out by his father and predecessor the monotheistic king Akhnaten.

The latter had called for the worship of only one deity, the sun god Aten, and the abandonment of the ancient Egyptians’ other gods.

When Akhnaten’s son Tutankhamun came to the throne, he returned Egypt to its traditional religion of worshipping a diverse set of deities at the top of which was the god Amun.

To ensure that this conversion continued after Tutankhamun’s death and to abort any further religious revolution, Ikram suggests in her paper that the priests mummified Tutankhamun’s corpse in an unusual way to make him appear as Osiris, the god of the afterlife and the land of Egypt.

Labels:

Afterlife,

Amun,

Mummies,

Mummification,

Osiris,

Penis,

Salima Ikram,

Tutankhamen

Sunday, September 1, 2013

Akhenaten: Egyptian Pharaoh, Nefertiti's Husband, Tut's Father

By Owen Jarus, LiveScience Contributor | August 30, 2013

Akhenaten was a pharaoh of Egypt who reigned over the country for about 17 years between roughly 1353 B.C. and 1335 B.C.

A religious reformer he made the Aten, the sun disc, the center of Egypt’s religious life and carried out an iconoclasm that saw the names of Amun, a pre-eminent Egyptian god, and his consort Mut, be erased from monuments and documents throughout Egypt’s empire.

When he ascended the throne his name was Amenhotep IV, but in his sixth year of rule he changed it to “Akhenaten” a name that the late Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat translated roughly as the “Benevolent one of (or for) the Aten.”

In honor of the Aten, he constructed an entirely new capital at an uninhabited place, which we now call Amarna, out in the desert. Its location was chosen so that its sunrise conveyed a symbolic meaning. “East of Amarna the sun rises in a break in the surrounding cliffs. In this landscape the sunrise could be literally ‘read’ as if it were the hieroglyph spelling Akhet-aten or ‘Horizon of the Aten’ — the name of the new city,” wrote Montserrat in his book "Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt" (Routledge, 2000).

He notes that this capital would quickly grow to become about 4.6 square miles (roughly 12 square kilometers) in size. After his death, the pharaoh’s religious reforms quickly collapsed, his new capital became abandoned and his successors denounced him.

Akhenaten, either before or shortly after he became pharaoh, would marry Nefertiti, who in some works of art is shown standing equal next to her husband. Some have even speculated that she may have become a co-, or even sole, ruler of Egypt.

Akhenaten was a pharaoh of Egypt who reigned over the country for about 17 years between roughly 1353 B.C. and 1335 B.C.

A religious reformer he made the Aten, the sun disc, the center of Egypt’s religious life and carried out an iconoclasm that saw the names of Amun, a pre-eminent Egyptian god, and his consort Mut, be erased from monuments and documents throughout Egypt’s empire.

When he ascended the throne his name was Amenhotep IV, but in his sixth year of rule he changed it to “Akhenaten” a name that the late Egyptologist Dominic Montserrat translated roughly as the “Benevolent one of (or for) the Aten.”

In honor of the Aten, he constructed an entirely new capital at an uninhabited place, which we now call Amarna, out in the desert. Its location was chosen so that its sunrise conveyed a symbolic meaning. “East of Amarna the sun rises in a break in the surrounding cliffs. In this landscape the sunrise could be literally ‘read’ as if it were the hieroglyph spelling Akhet-aten or ‘Horizon of the Aten’ — the name of the new city,” wrote Montserrat in his book "Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt" (Routledge, 2000).

He notes that this capital would quickly grow to become about 4.6 square miles (roughly 12 square kilometers) in size. After his death, the pharaoh’s religious reforms quickly collapsed, his new capital became abandoned and his successors denounced him.

Akhenaten, either before or shortly after he became pharaoh, would marry Nefertiti, who in some works of art is shown standing equal next to her husband. Some have even speculated that she may have become a co-, or even sole, ruler of Egypt.

Labels:

Akhenaten,

Amarna,

Amenhotep IV,

Amun,

Art,

Aten,

Biographies,

Mut,

Nefertiti,

New Kingdom,

Pharaohs,

Religion,

Tutankhamen

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Luxor: Ancient Egyptian Capital

by Owen Jarus, LiveScience ContributorDate: 25 June 2013

Luxor is a modern-day Egyptian city that lies atop an ancient city that the Greeks named “Thebes” and the ancient Egyptians called “Waset.”

Located in the Nile River about 312 miles (500 kilometers) south of Cairo the World Gazetteer website reports that, as of the 2006 census, Luxor and its environs had a population of more than 450,000 people. The name Luxor “derives from the Arabic al-uksur, ‘the fortifications,’ which in turn was adapted from the Latin castrum,” which refers to a Roman fort built in the area, writes William Murnane in the "Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt" (Oxford University Press, 2001).

The ancient city of Luxor served at times as Egypt’s capital and became one of its largest urban centers. “On the East Bank, beneath the modern city of Luxor, lie the remains of an ancient town that from about 1500 to 1000 B.C. was one of the most spectacular in Egypt, with a population of perhaps 50,000,” write archaeologists Kent Weeks and Nigel Hetherington in their book "The Valley of the Kings Site Management Masterplan" (Theban Mapping Project, 2006).

In ancient times, the city was known as home to the god Amun, a deity who became associated with Egyptian royalty. In turn, during Egypt’s “New Kingdom” period between roughly 1550-1050 B.C., most of Egypt’s rulers chose to be buried close to the city in the nearby Valley of the Kings. Other famous sites near the city, which were built or greatly expanded during the New Kingdom period, include Karnak Temple, Luxor Temple, the Valley of the Queens and Queen Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir al-Bahari.

“Of all the ancient cities, no other city reached the glory of Thebes in supremacy,” writes Egyptologist Rasha Soliman in her book "Old and Middle Kingdom Theban Tombs" (Golden House Publications, 2009). “Thebes is the largest and wealthiest heritage site in the world.”

Luxor is a modern-day Egyptian city that lies atop an ancient city that the Greeks named “Thebes” and the ancient Egyptians called “Waset.”

Located in the Nile River about 312 miles (500 kilometers) south of Cairo the World Gazetteer website reports that, as of the 2006 census, Luxor and its environs had a population of more than 450,000 people. The name Luxor “derives from the Arabic al-uksur, ‘the fortifications,’ which in turn was adapted from the Latin castrum,” which refers to a Roman fort built in the area, writes William Murnane in the "Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt" (Oxford University Press, 2001).

The ancient city of Luxor served at times as Egypt’s capital and became one of its largest urban centers. “On the East Bank, beneath the modern city of Luxor, lie the remains of an ancient town that from about 1500 to 1000 B.C. was one of the most spectacular in Egypt, with a population of perhaps 50,000,” write archaeologists Kent Weeks and Nigel Hetherington in their book "The Valley of the Kings Site Management Masterplan" (Theban Mapping Project, 2006).

In ancient times, the city was known as home to the god Amun, a deity who became associated with Egyptian royalty. In turn, during Egypt’s “New Kingdom” period between roughly 1550-1050 B.C., most of Egypt’s rulers chose to be buried close to the city in the nearby Valley of the Kings. Other famous sites near the city, which were built or greatly expanded during the New Kingdom period, include Karnak Temple, Luxor Temple, the Valley of the Queens and Queen Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir al-Bahari.

“Of all the ancient cities, no other city reached the glory of Thebes in supremacy,” writes Egyptologist Rasha Soliman in her book "Old and Middle Kingdom Theban Tombs" (Golden House Publications, 2009). “Thebes is the largest and wealthiest heritage site in the world.”

Labels:

Amun,

Deir el-Medina,

Karnak,

Luxor,

Luxor Temple,

Mentuhotep,

New Kingdom,

Thebes,

Valley Of The Kings,

Valley Of The Queens,

Waset

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Museum Pieces - Sphinx of Shepenupet II

|

| Photocredit: Jürgen Liepe |

Statue

25th Dynasty (Kushite)

Karnak (Tempel)

Granit

46 x 25 x 83 cm

120 kg

Ident.Nr. ÄM 7972

Shepenupet II (alt. Shepenwepet II, prenomen: Henutneferumut Irietre) was an Ancient Egyptian princess of the Twenty-fifth dynasty and the Divine Adoratrice of Amun from around 700 BC to 650 BC. She was the daughter of the first Kushite pharaoh Piye, and sister of Piye's successors Taharqa and Shabaka. She was adopted by her predecessor in office, Amenirdis I, a sister of Piye. Shepenupet was God's Wife from the beginning of Taharqa's reign until Year 9 of Pharaoh Psamtik I. While in office she had to come to a power sharing arrangement with the mayor of Thebes, Montuemhet.

Her niece Amenirdis, the daughter of Taharqa, was appointed as her heiress. Shepenupet was compelled to adopt Nitocris, daughter of pharaoh Psamtik I who reunited Egypt after the Assyrian conquest. This is evidenced by the so-called Adoption Stela of Nitocris. In 656 BC, in Year 9 of the reign of Psamtik I, she received Nitocris at Thebes.

Her tomb is located in the grounds of Medinet Habu. She was succeeded by Amenirdis II who was succeeded by Nitocris I.

Sources: Ägyptisches Museum, wikipedia.org

Labels:

25th Dynasty,

Amenirdis I,

Amun,

Art,

Museum Pieces,

Museums and Exhibitions,

Piye,

Psamtik I,

Shabaqo,

Shepenupet II,

Taharqa

Friday, February 1, 2013

Sudan’s Nubian pyramids: Gebel Barkal and Napata

Ancient Egyptians had their own version of 'Mount Olympus' in Gebel Barkal in Sudan which served as the house of god Amon

by Mohammed Elrazzaz, Thursday 31 Jan 2013

The Greeks were not the first to have a "Mount Olympus" where their pantheon of gods resided. Long before them, the Ancient Egyptians had their own version of Mount Olympus, but it was neither located in Greece nor Egypt. Named Gebel Barkal, the holy mountain in Sudan served as the place where the god Amon lived.

Old capital of Napata

The Kushite Kingdom is in fact two kingdoms: one that had its birth pangs around 2500 BC and underwent a serious downfall in the mid-second millennium BC when its political power alarmed its Egyptian neighbours, and a second kingdom that rose in the mid-eleventh century BC and lasted till the fourth century AD.

Crossing the Bayuda Desert, we slowly approached the first of five archaeological sites collectively known as Gebel Barkal and the Napata Region. Napata was the capital of Kush between the eighth and third centuries BC, lending its name to the flourishing Napata culture. This very same spot was the birthplace of the Black Pharaohs that ruled Egypt between the eighth and seventh centuries BC.

by Mohammed Elrazzaz, Thursday 31 Jan 2013

The Greeks were not the first to have a "Mount Olympus" where their pantheon of gods resided. Long before them, the Ancient Egyptians had their own version of Mount Olympus, but it was neither located in Greece nor Egypt. Named Gebel Barkal, the holy mountain in Sudan served as the place where the god Amon lived.

Old capital of Napata

The Kushite Kingdom is in fact two kingdoms: one that had its birth pangs around 2500 BC and underwent a serious downfall in the mid-second millennium BC when its political power alarmed its Egyptian neighbours, and a second kingdom that rose in the mid-eleventh century BC and lasted till the fourth century AD.

Crossing the Bayuda Desert, we slowly approached the first of five archaeological sites collectively known as Gebel Barkal and the Napata Region. Napata was the capital of Kush between the eighth and third centuries BC, lending its name to the flourishing Napata culture. This very same spot was the birthplace of the Black Pharaohs that ruled Egypt between the eighth and seventh centuries BC.

Labels:

25th Dynasty,

Amun,

Gebel Barkal,

Kush,

Monuments,

Napata,

Piankhi,

Pyramids,

Taharqa

Friday, January 11, 2013

Out of the sea

Jenny Jobbins looks at the regional myths that ancient Egyptians associated with the creation of the world and finds an uncanny parallel with what science teaches us today

The Egyptians believed that the various ramifications of the sun god — Horus, the rising sun; Ra and Ra-Harakhte, the full sun; and Osiris, the setting sun — governed their lives and the lives of all living animals and plants. But how did they explain the creation of that world?

Their theory of creation depended on where — and, to some extent, when — they lived, and was woven around the cults of the different regional divinities. The main cult centres were in Hermopolis, Heliopolis, Memphis and Thebes.

To some extent there were common factors in these regional myths. In the beginning was chaos, envisaged as a vast ocean called Nu. From these waters rose a primaeval land mound, the pyramid-shaped benben, and at the same time life emerged from the benben’s rich, alluvial soil.

THE ENNEAD OF HELIOPOLIS: If you were born during the Old Kingdom in the area around Heliopolis, just to the northeast of modern Cairo, you would have grown up in the midst of a spiritually and politically charged atmosphere in the shade of the temple at the centre of the cult of Ra-Harakhte. Only one remnant remains today of this temple, Egypt’s first known temple to the sun god: the obelisk of Senusert I.

The people of Heliopolis (ancient Iwnw) attributed the creation to Atum, a deity who was associated with the sun-god Ra. Atum was the first god: he created himself, emerging on the primaeval mound from the water, Nu. According to the Heliopolitan myth, Atum single-handedly created his progeny, each with an element linked to the physical world. First he sneezed the air god with the onomatopoeic name of Shu, and spat out Shu’s sister, Tefnut. Shu and Tefnut were the parents of Geb, the Earth god, and Nut, the sky goddess. Despite being separated by their father, Shu, Geb and Nut nevertheless produced Isis, goddess of motherhood; Osiris, god of vegetation and resurrection; Set, god of the desert and of storms; and the protector goddess Nephtys. These nine gods, the family of the omnipotent Atum, formed the Ennead of Heliopolis. The hierarchy was perpetuated through the Pyramid Texts, which accompanied the deceased pharaoh and instructed him on how to conduct himself on his passage to the afterlife.

Horus, son of Isis and Osiris, and Anubis, son of Set and Nephtys, were the offspring of the last four members of the original Ennead.

The Egyptians believed that the various ramifications of the sun god — Horus, the rising sun; Ra and Ra-Harakhte, the full sun; and Osiris, the setting sun — governed their lives and the lives of all living animals and plants. But how did they explain the creation of that world?

Their theory of creation depended on where — and, to some extent, when — they lived, and was woven around the cults of the different regional divinities. The main cult centres were in Hermopolis, Heliopolis, Memphis and Thebes.

To some extent there were common factors in these regional myths. In the beginning was chaos, envisaged as a vast ocean called Nu. From these waters rose a primaeval land mound, the pyramid-shaped benben, and at the same time life emerged from the benben’s rich, alluvial soil.

THE ENNEAD OF HELIOPOLIS: If you were born during the Old Kingdom in the area around Heliopolis, just to the northeast of modern Cairo, you would have grown up in the midst of a spiritually and politically charged atmosphere in the shade of the temple at the centre of the cult of Ra-Harakhte. Only one remnant remains today of this temple, Egypt’s first known temple to the sun god: the obelisk of Senusert I.

The people of Heliopolis (ancient Iwnw) attributed the creation to Atum, a deity who was associated with the sun-god Ra. Atum was the first god: he created himself, emerging on the primaeval mound from the water, Nu. According to the Heliopolitan myth, Atum single-handedly created his progeny, each with an element linked to the physical world. First he sneezed the air god with the onomatopoeic name of Shu, and spat out Shu’s sister, Tefnut. Shu and Tefnut were the parents of Geb, the Earth god, and Nut, the sky goddess. Despite being separated by their father, Shu, Geb and Nut nevertheless produced Isis, goddess of motherhood; Osiris, god of vegetation and resurrection; Set, god of the desert and of storms; and the protector goddess Nephtys. These nine gods, the family of the omnipotent Atum, formed the Ennead of Heliopolis. The hierarchy was perpetuated through the Pyramid Texts, which accompanied the deceased pharaoh and instructed him on how to conduct himself on his passage to the afterlife.

Horus, son of Isis and Osiris, and Anubis, son of Set and Nephtys, were the offspring of the last four members of the original Ennead.

Friday, August 31, 2012

Religion in the Lives of the Ancient Egyptians

by Emily Teeter & Douglas J. Brewer

Because the role of religion in Euro-American culture differs so greatly from that in ancient Egypt, it is difficult to fully appreciate its significance in everyday Egyptian life. In Egypt, religion and life were so interwoven that it would have been impossible to be agnostic. Astronomy, medicine, geography, agriculture, art, and civil law--virtually every aspect of Egyptian culture and civilization--were manifestations of religious beliefs.

Most aspects of Egyptian religion can be traced to the people's observation of the environment. Fundamental was the love of sunlight, the solar cycle and the comfort brought by the regular rhythms of nature, and the agricultural cycle surrounding the rise and fall of the Nile. Egyptian theology attempted, above all else, to explain these cosmic phenomena, incomprehensible to humans, by means of a series of understandable metaphors based upon natural cycles and understandable experiences. Hence, the movement of the sun across the sky was represented by images of the sun in his celestial boat crossing the vault of heaven or of the sun flying over the sky in the form of a scarab beetle. Similarly, the concept of death was transformed from the cessation of life into a mirror image of life wherein the deceased had the same material requirements and desires.

Origins and nature of the gods

It is almost impossible to enumerate the gods of the Egyptians, for individual deities could temporarily merge with each other to form syncretistic gods (Amun-Re, Re-Harakhty, Ptah-Sokar, etc.) who combined elements of the individual gods. A single god might also splinter into a multiplicity of forms (Amun-em-Opet, Amun-Ka-Mutef, Amun of Ipet-swt), each of whom had an independent cult and role. Unlike the gods of the Graeco-Roman world, most Egyptian gods had no definite attributes. For example, Amun, one of the most prominent deities of the New Kingdom and Late Period, is vaguely referred to in secondary literature as the "state god" because his powers were so widespread and encompassing as to be indefinable.

To a great extent, gods were patterned after humans--they were born, some died (and were reborn), and they fought amongst themselves. Yet as much as the gods' behavior resembled human behavior, they were immortal and always superior to humans.

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Tomb of the Chantress

by Julian Smith

A newly discovered burial chamber in the Valley of the Kings provides a rare glimpse into the life of an ancient Egyptian singer

A newly discovered burial chamber in the Valley of the Kings provides a rare glimpse into the life of an ancient Egyptian singer

On January 25, 2011, tens of thousands of protestors flooded Cairo’s Tahrir Square, demanding the end of President Hosni Mubarak’s regime. As the “day of revolt” filled the streets of Cairo and other cities with tear gas and flying stones, a team of archaeologists led by Susanne Bickel of the University of Basel in Switzerland was about to make one of the most significant discoveries in the Valley of the Kings in almost a century.

The valley lies on the west bank of the Nile, opposite what was once Egypt’s spiritual center—the city of Thebes, now known as Luxor. The valley was the final resting place of the pharaohs and aristocracy beginning in the New Kingdom period (1539–1069 B.C.), when Egyptian wealth and power were at a high point. Dozens of tombs were cut into the valley’s walls, but most of them were eventually looted. It was in this place that the Basel team came across what they initially believed to be an unremarkable find.

At the southeastern end of the valley they discovered three sides of a man-made stone rim surrounding an area of about three-and-a-half by five feet. The archaeologists suspected that it was just the top of an abandoned shaft. But, because of the uncertainty created by Egypt’s political revolution, they covered the stone rim with an iron door while they informed the authorities and applied for an official permit to excavate.

A year later, just before the first anniversary of the revolution, Bickel returned with a team of two dozen people, including field director Elina Paulin-Grothe of the University of Basel, Egyptian inspector Ali Reda, and local workmen. They started clearing the sand and gravel out of the shaft. Eight feet down, they came upon the upper edge of a door blocked by large stones. At the bottom of the shaft they found fragments of pottery made from Nile silt and pieces of plaster, a material commonly used to seal tomb entrances. Those plaster pieces, together with the age of other nearby sites, were the first sign that the shaft might actually be a tomb dating to between 1539 and 1292 B.C., Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty. The large stones appeared to have been added later.

Labels:

Afterlife,

Amun,

Coffin,

Luxor,

New Kingdom,

Third Intermediate Period,

Tomb,

Valley Of The Kings

Thursday, May 10, 2012

The Divine King

In Ancient Egyptian times Pharaohs went to some measures to justify their claims to the throne. During the 18th Dynasty for example, kings legitimized their kingship through the myth of the birth of the divine king. They were fathered by a god, not by a man. Amun was the god to be fathered by. Pointing out the importance of the cult of Amun at Karnak during the 18th Dynasty, with a small downfall during the reign of Akhenaten.

So did Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC) after he completed one of his additions to the Karnak temple in honour of Amun he placed the so called coronation inscription to prove his divinity:

I am his son, beloved of his majesty, whom his double desires to cause that I should present this land at the place, where he is. .. I requited his beauty with something greater than it by magnifying him more than the gods. The recompense of him who does excellent things is a reward for him of things more excellent than they. I have built his house as an eternal work. - my father caused that I should be divine, that I might extend the throne of him who made me; that I might supply with food his altars upon earth; that I might make to flourish for him the sacred slaughtering-block with great slaughters in his temple, consisting of oxen and calves without limit. .. -for this temple of my father Amun, at all feasts; of the sixth day satisfied with that which he desired should be. I know that it is forever; that Thebes is eternal. Amun, Lord of Karnak, Re of Heliopolis of the South, his glorious eye which is in this land. (Ancient Records Of Egypt - J.H. Breasted, Volume II, § 149)

Also Queen Hatshepsut (1473-1458 BC) legitimized her kingship through the myth of divine conception and birth. According to inscriptions, Amun himself chose her to become the ruler of Egypt, even before she was born. One inscription tells the story about how Hatshepsut's mother Queen Ahmose became pregnant of her daughter. The god Amun took form of Hatshepsut's father Thutmose I and found Queen Ahmose asleep in her bedroom. She woke up by the fragrance of the god and recognized him as a god. They had intercourse and Hatshepsut was conceived. The inscription later tells:

Utterance of Amun, Lord of the Two Lands, before her: "Khnemet-Amun-Hatshepsut shall be the name of this my daughter, whom I have placed in thy body, this saying which comes out of thy mouth. She shall exercise the excellent kingship in this whole land. My soul is hers, my bounty is hers, my crown is hers, that she may rule the Two Lands, that she may lead all the living." (Ancient Records Of Egypt - J.H. Breasted, Volume II, § 198)

These are just two examples of two kings from the 18th dynasty, but the divine birth was easily adopted by later Pharaohs. Even in Ptolemaic times, and by Alexander the Great when he visited the Oracle of Amun at Siwa he was proclaimed as son of Amun. Alexander was simply using the old existing tradition. Nothing new there.

By Amun-Ra

Labels:

18th Dynasty,

Amun,

Hatshepsut,

Karnak,

Kingship,

New Kingdom,

Religion,

Thutmose III

Sunday, February 26, 2012

The 25th Dynasty

by Timothy Kendall

The Nubian Conquest of Egypt: 1080-650 BC

Egyptian control over Nubia lapsed after the death of Ramesses II (ca. 1224 BC), just as the pharaoh's control over Egypt itself began to wane. In the early eleventh century BC Egypt split into two semi-autonomous domains: Lower Egypt was governed by the pharaoh, and the much larger tract of Upper Egypt was governed in the name of the god Amun by his high priest at Thebes. Nubia's last imperial viceroy, Panehesy ("The Nubian") became a renegade by waging war against the Theban high priests who were themselves military commanders seeking to extend their authority southward. By early Dynasty 21, most of Lower Nubia had become a no-man's land. Upper Nubia (the northern Sudan) became independent under authorities unknown.

From the meager data available, it would appear that those who ultimately gained control in Upper Nubia were people who had been little influenced by Egyptian culture. The old centers of the New Kingdom show poor continuity of occupation, and their temples became derelict.

Not until Dynasty 22 are African products again listed among gifts dedicated to Amun of Karnak by an Egyptian king. The donor, Sheshonq I (ca. 945-924 BC), and his successor Osorkon I (ca. 924-889 BC) are also said in the Bible to have employed Kushite mercenaries and officers in their campaigns against Judah. Assyrian texts of the later ninth century further note that the pharaohs were sending African products to the Assyrian kings. Such evidence suggests that the Egyptians during this period had re-established trade relations with the far south, but they never reveal with whom they were dealing. One can only assume that from the tenth century on one or more dominant chiefdoms had emerged in Nubia - again, as in the case of Kerma centuries before, beginning a process of material, cultural, and political enrichment through commerce with Egypt.

The Nubian Conquest of Egypt: 1080-650 BC

Egyptian control over Nubia lapsed after the death of Ramesses II (ca. 1224 BC), just as the pharaoh's control over Egypt itself began to wane. In the early eleventh century BC Egypt split into two semi-autonomous domains: Lower Egypt was governed by the pharaoh, and the much larger tract of Upper Egypt was governed in the name of the god Amun by his high priest at Thebes. Nubia's last imperial viceroy, Panehesy ("The Nubian") became a renegade by waging war against the Theban high priests who were themselves military commanders seeking to extend their authority southward. By early Dynasty 21, most of Lower Nubia had become a no-man's land. Upper Nubia (the northern Sudan) became independent under authorities unknown.

From the meager data available, it would appear that those who ultimately gained control in Upper Nubia were people who had been little influenced by Egyptian culture. The old centers of the New Kingdom show poor continuity of occupation, and their temples became derelict.

Not until Dynasty 22 are African products again listed among gifts dedicated to Amun of Karnak by an Egyptian king. The donor, Sheshonq I (ca. 945-924 BC), and his successor Osorkon I (ca. 924-889 BC) are also said in the Bible to have employed Kushite mercenaries and officers in their campaigns against Judah. Assyrian texts of the later ninth century further note that the pharaohs were sending African products to the Assyrian kings. Such evidence suggests that the Egyptians during this period had re-established trade relations with the far south, but they never reveal with whom they were dealing. One can only assume that from the tenth century on one or more dominant chiefdoms had emerged in Nubia - again, as in the case of Kerma centuries before, beginning a process of material, cultural, and political enrichment through commerce with Egypt.

Labels:

25th Dynasty,

Amun,

Gebel Barkal,

Kingship,

Kush,

Napata,

Nubia,

Piye,

Shabaqo,

Taharqa,

Third Intermediate Period

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)